15 октября в США объявили финалистов престижной американской литературной премии — Национальной книжной премии. В короткий список в четырех номинациях попадают по 5 номинантов (в длинном списке было по 10). Победители будут названы 20 ноября на торжественной церемонии в Манхэттене.

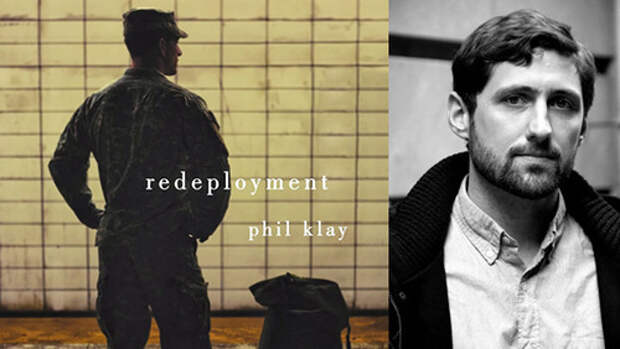

В числе претендентов на главный приз в номинации "Художественна литература" книга Фила Клэя, морпеха и ветерана войны в Ираке.***

"Marines and soldiers don't issue themselves orders, they don't send themselves overseas," says former Marine Phil Klay. "United States citizens elect the leaders who send us overseas."

“The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are as much every U.S. citizen's wars as they are the veterans' wars.

- Phil Klay

In his new collection, Redeployment, Klay, who served in Iraq, tells a dozen vivid stories about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan from the perspectives of the people who experienced it — combatants, civilians and children alike. Taken together, the stories give a grim — and occasionally funny — picture of war and what happens next to those who survive it. Once the soldiers return home, Klay says, that dialogue between veterans and civilians is essential.

"The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are as much every U.S. citizen's wars as they are the veterans' wars," Klay tells NPR's Linda Wertheimer. "If we don't assume that civilians have just as much ownership and the moral responsibilities that we have as a nation when we embark on something like that, then we're in a very bad situation. "

***

On telling the story from several perspectives

I decided very early on it was going to be all first-person narratives. A lot of times you're interacting with people for whom you're one of the very few veterans that they've met or had a lot of interactions with, and there's a temptation for you to feel like you can pontificate about what the experience was or what it meant, and that leads to a lot of nonsense. I wanted to have very different viewpoints, very different experiences, just so the reader could kind of think about what they were trying to say and how they clash with each other. There's not a single narrative about this war.

On his own homecoming

I don't want to act as though my deployment was particularly rough, because it wasn't. I had a very mild deployment; I was a staff officer. But just a few days before [I returned to the U.S.] I'd seen people coming into the medical facility ... horribly injured. And then a few days later I'm walking down Madison Avenue in the summer and there's just zero sense that we're at war. It's very strange and difficult to deal with the disconnect. And, of course, if veterans just talk to each other about wars, then that disconnect's only going to continue.

On how veterans must be able to share their experiences with civilians

You know, this is not the World War II generation. We have a much smaller percentage of the population that has gone overseas. But also I think it's important personally — the notion that you can't communicate these very intense experiences. It just means that veterans are going to be isolated, that something incredibly important to them that they went through, something that they can't share, you know, with their friends and family who didn't serve, and I don't think that's true, and I think that that isolation's a terrible thing to feel.

On why he wrote the book

What I really want — and I think what a lot of veterans want — is a sense of serious engagement with the wars, because it's important, because it matters, because lives are at stake, and it's something we did as a nation. That's something that deserves to be thought about very seriously and very honestly, without resorting to the sort of comforting stories that allow us to tie a bow on the experience and move on.

***

Excerpt: Redeployment

Redeployment

We shot dogs. Not by accident. We did it on purpose, and we called it Operation Scooby. I'm a dog person, so I thought about that a lot.

First time was instinct. I hear O'Leary go, "Jesus," and there's a skinny brown dog lapping up blood the same way he'd lap up water from a bowl. It wasn't American blood, but still, there's that dog, lapping it up. And that's the last straw, I guess, and then it's open season on dogs.

At the time, you don't think about it. You're thinking about who's in that house, what's he armed with, how's he gonna kill you, your buddies. You're going block by block, fighting with rifles good to 550 meters, and you're killing people at five in a concrete box.

The thinking comes later, when they give you the time. See, it's not a straight shot back, from war to the Jacksonville mall. When our deployment was up, they put us on TQ, this logistics base out in the desert, let us decompress a bit. I'm not sure what they meant by that. Decompress. We took it to mean jerk off a lot in the showers. Smoke a lot of cigarettes and play a lot of cards. And then they took us to Kuwait and put us on a commercial airliner to go home.

So there you are. You've been in a no-shit war zone and then you're sitting in a plush chair, looking up at a little nozzle shooting air-conditioning, thinking, What the fuck? You've got a rifle between your knees, and so does everyone else. Some Marines got M9 pistols, but they take away your bayonets because you aren't allowed to have knives on an airplane. Even though you've showered, you all look grimy and lean. Everybody's hollow-eyed, and their cammies are beat to shit. And you sit there, and close your eyes, and think.

The problem is, your thoughts don't come out in any kind of straight order. You don't think, Oh, I did A, then B, then C, then D. You try to think about home, then you're in the torture house. You see the body parts in the locker and the retarded guy in the cage. He squawked like a chicken. His head was shrunk down to a coconut. It takes you a while to remember Doc saying they'd shot mercury into his skull, and then it still doesn't make any sense.

You see the things you saw the times you nearly died. The broken television and the hajji corpse. Eicholtz covered in blood. The lieutenant on the radio.

You see the little girl, the photographs Curtis found in a desk. First had a beautiful Iraqi kid, maybe seven or eight years old, in bare feet and a pretty white dress like it's First Communion. Next she's in a red dress, high heels, heavy makeup. Next photo, same dress, but her face is smudged and she's holding a gun to her head.

I tried to think of other things, like my wife, Cheryl. She's got pale skin and fine dark hairs on her arms. She's ashamed of them, but they're soft. Delicate.

But thinking of Cheryl made me feel guilty, and I'd think about Lance Corporal Hernandez, Corporal Smith, and Eicholtz. We were like brothers, Eicholtz and me. The two of us saved this Marine's life one time. A few weeks later, Eicholtz is climbing over a wall. Insurgent pops out a window, shoots him in the back when he's halfway over.

So I'm thinking about that. And I'm seeing the retard, and the girl, and the wall Eicholtz died on. But here's the thing. I'm thinking a lot, and I mean a lot, about those fucking dogs.

And I'm thinking about my dog. Vicar. About the shelter we'd got him from, where Cheryl said we had to get an older dog because nobody takes older dogs. How we could never teach him anything. How he'd throw up shit he shouldn't have eaten in the first place. How he'd slink away all guilty, tail down and head low and back legs crouched. How his fur started turning gray two years after we got him, and he had so many white hairs on his face that it looked like a mustache.

So there it was. Vicar and Operation Scooby, all the way home.

Maybe, I don't know, you're prepared to kill people. You practice on man-shaped targets so you're ready. Of course, we got targets they call "dog targets." Target shape Delta. But they don't look like fucking dogs.

And it's not easy to kill people, either. Out of boot camp, Marines act like they're gonna play Rambo, but it's fucking serious, it's professional. Usually. We found this one insurgent doing the death rattle, foaming and shaking, fucked up, you know? He's hit with a 7.62 in the chest and pelvic girdle; he'll be gone in a second, but the company XO walks up, pulls out his KA-BAR, and slits his throat. Says, "It's good to kill a man with a knife." All the Marines look at each other like, "What the fuck?" Didn't expect that from the XO. That's some PFC bullshit.

On the flight, I thought about that, too.

It's so funny. You're sitting there with your rifle in your hands but no ammo in sight. And then you touch down in Ireland to refuel. And it's so foggy you can't see shit, but, you know, this is Ireland, there's got to be beer. And the plane's captain, a fucking civilian, reads off some message about how general orders stay in effect until you reach the States, and you're still considered on duty. So no alcohol.

Well, our CO jumped up and said, "That makes about as much sense as a goddamn football bat. All right, Marines, you've got three hours. I hear they serve Guinness." Ooh-fucking-rah.

Corporal Weissert ordered five beers at once and had them laid out in front of him. He didn't even drink for a while, just sat there looking at 'em all, happy. O'Leary said, "Look at you, smiling like a faggot in a dick tree," which is a DI expression Curtis loves.

So Curtis laughs and says, "What a horrible fucking tree," and we all start cracking up, happy just knowing we can get fucked up, let our guard down.

We got crazy quick. Most of us had lost about twenty pounds and it'd been seven months since we'd had a drop of alcohol. MacManigan, second award PFC, was rolling around the bar with his nuts hanging out of his cammies, telling Marines, "Stop looking at my balls, faggot." Lance Corporal Slaughter was there all of a half hour before he puked in the bathroom, with Corporal Craig, the sober Mormon, helping him out, and Lance Corporal Greeley, the drunk Mormon, puking in the stall next to him. Even the Company Guns got wrecked.

It was good. We got back on the plane and passed the fuck out. Woke up in America.

Except when we touched down in Cherry Point, there was nobody there. It was zero dark and cold, and half of us were rocking the first hangover we'd had in months, which at that point was a kind of shitty that felt pretty fucking good. And we got off the plane and there's a big empty landing strip, maybe a half dozen red patchers and a bunch of seven tons lined up. No families.

The Company Guns said that they were waiting for us at Lejeune. The sooner we get the gear loaded on the trucks, the sooner we see 'em.

Roger that. We set up working parties, tossed our rucks and seabags into the seven tons. Heavy work, and it got the blood flowing in the cold. Sweat a little of the alcohol out, too.

Then they pulled up a bunch of buses and we all got on, packed in, M16s sticking everywhere, muzzle awareness gone to shit, but it didn't matter.

Cherry Point to Lejeune's an hour. First bit's through trees. You don't see much in the dark. Not much when you get on 24, either. Stores that haven't opened yet. Neon lights off at the gas stations and bars. Looking out, I sort of knew where I was, but I didn't feel home. I figured I'd be home when I kissed my wife and pet my dog.

We went in through Lejeune's side gate, which is about ten minutes away from our battalion area. Fifteen, I told myself, way this fucker is driving. When we got to McHugh, everybody got a little excited. And then the driver turned on A Street. Battalion area's on A, and I saw the barracks and I thought, There it is. And then they stopped about four hundred meters short. Right in front of the armory. I could've jogged down to where the families were. I could see there was an area behind one of the barracks where they'd set up lights. And there were cars parked everywhere. I could hear the crowd down the way. The families were there. But we all got in line, thinking about them just down the way. Me thinking about Cheryl and Vicar. And we waited.

When I got to the window and handed in my rifle, though, it brought me up short. That was the first time I'd been separated from it in months. I didn't know where to rest my hands. First I put them in my pockets, then I took them out and crossed my arms, and then I just let them hang, useless, at my sides.

After all the rifles were turned in, First Sergeant had us get into a no-shit parade formation. We had a fucking guidon waving out front, and we marched down A Street. When we got to the edge of the first barracks, people started cheering. I couldn't see them until we turned the corner, and then there they were, a big wall of people holding signs under a bunch of outdoor lights, and the lights were bright and pointed straight at us, so it was hard to look into the crowd and tell who was who. Off to the side there were picnic tables and a Marine in woodlands grilling hot dogs. And there was a bouncy castle. A fucking bouncy castle.

We kept marching. A couple more Marines in woodlands were holding the crowd back in a line, and we marched until we were straight alongside the crowd, and then First Sergeant called us to a halt.

I saw some TV cameras. There were a lot of U.S. flags. The whole MacManigan clan was up front, right in the middle, holding a banner that read: OO-RAH PRIVATE FIRST CLASS BRADLEY MACMANIGAN. WE ARE SO PROUD.

I scanned the crowd back and forth. I'd talked to Cheryl on the phone in Kuwait, not for very long, just, "Hey, I'm good," and, "Yeah, within forty-eight hours. Talk to the FRO, he'll tell you when to be there." And she said she'd be there, but it was strange, on the phone. I hadn't heard her voice in a while.

Then I saw Eicholtz's dad. He had a sign, too. It said: WELCOME BACK HEROES OF BRAVO COMPANY. I looked right at him and remembered him from when we left, and I thought, That's Eicholtz's dad. And that's when they released us. And they released the crowd, too.

I was standing still, and the Marines around me, Curtis and O'Leary and MacManigan and Craig and Weissert, they were rushing out to the crowd. And the crowd was coming forward. Eicholtz's dad was coming forward.

He was shaking the hand of every Marine he passed. I don't think a lot of guys recognized him, and I knew I should say something, but I didn't. I backed off. I looked around for my wife. And I saw my name on a sign: SGT PRICE, it said. But the rest was blocked by the crowd, and I couldn't see who was holding it. And then I was moving toward it, away from Eicholtz's dad, who was hugging Curtis, and I saw the rest of the sign. It said: SGT PRICE, NOW THAT YOU'RE HOME YOU CAN DO SOME CHORES. HERE'S YOUR TO-DO LIST. 1) ME. 2) REPEAT NUMBER 1.

Источник - http://www.npr.org